The shoes, a clean shirt and all the bits in-between, would be

accompanying me a little later to see the bank manager about my

overdraft. It seemed like a good investment to make and I certainly

didn’t want to leave the wrong kind of deposit on the floor.

So, under the sink in the kitchen for the bottle of Old Mrs Smoker’s

Patent shoe-liquid, a small brush and a rag. The brush, the small bottle

of Mrs S and… a tee shirt. In fact, under that sink in the kitchen, in

that hard to get to cupboard reserved for polish, squeezo and bug-spray,

I found a whole nest of tee shirts.

Now, Mrs Lenox likes to keep her memories in photo albums, and we

have a camera for this. We also have a shelf packed full of volumes of

nostalgia, baby pictures and people grinning whitely at the flash.

Whereas I prefer to have my closest moments emblazoned across my chest

and following this stored lovingly in my drawer. So I was surprised to

see a pile of treasures, old memories, drunken sprees, exotic dancing

women and other things that go up to make a gentleman’s life complete,

images in cotton rather than film, all stacked under the sink.

‘Ah’, I mourned, as I pulled out the first one, covered in old silver

polish and grime, with a few really quite small holes in it, ‘but this

one comes from my trip to Mexico’. But worse was to come. My cycle-trip

across Britain was next: Land’s End to John of Groats with the ‘Fentiman

Flyers’. We had cycled all that way when I was about 34 and could still

do that sort of thing, while eating, drinking and smoking along the

entire route. It was my only trip I’d ever done in Britain (besides the

regular train trip to school in the sixties) and now, all that was left

was the old tee-shirt, stained and unloved.

Others followed. A set that I’d printed up myself on the occasion of

the first ever Moors and Christians in Mojácar, which like so many

traditions around here, is not as old as one might think. I had printed

300, sold about four and the bulk of the remainder were there, under the

blasted sink.

Tee shirts are a relatively new invention. They are simply

under-vests with a message or picture on them. Plain white ones had

become respectable with Marlon Brando and the decorated versions

followed along in America in around 1965 and in Europe a few years

later. Tee shirts are a way to make a statement which, unlike tattoos,

is easily removable at the end of the evening. We have political tee

shirts (Vote for me), funny tee shirts (Vote for them), protest tee shirts (Don’t vote for them), nihilist tee shirts (Don’t vote!), existential tee shirts (Why vote?) and explanatory tee shirts (It’s their country, like. Know what I mean?).

Oh, and wet t-shirts (spelt the American way since they are

inexplicably more popular in Miami than in Mojácar), which, on

reflection, get my vote.

But before these all came along, and these garments were merely white

and worn under a shirt, the hippies invented the tie-dye. You took a

tee shirt and wrapped a few rubber bands or tied bits of string around

chunks of it, maybe sealed a pinch in a plastic bag, all tightly

knotted, and put the whole thing into a boiling pot of dye, available

for three pesetas in all the better drogerias. Boil for a

while, or until your mother came rushing into the kitchen, douse in cold

salty water (was it? Or did the salt go into the first pot?), untie the

bits of string and, hey presto. A mungy looking mess!

Let your hair grow long, wear some Goulimine beads, sit cross-legged

on the floor while picking out the best buds on the cardboard cover of a

Santana album (try and do that on a CD), roll a doobie and hope that no

on e notices your tie-dyed tee shirt came out a bit wonky.

e notices your tie-dyed tee shirt came out a bit wonky.

Well, that cultural phenomenon didn’t last long.

But the idea did. The lowly undergarment – less its cousin, the

string-vest that only an Englishman could wear – was coming of age. It

started to have colour and began to be worn alone. Well, when the

weather permitted. It was only a matter of time before someone came up

with catchy designs and words. Including endless copies of Che Guevara

looking beatific; some very silly ones (‘I’m with stupid’ and ‘My parents went to Albox…’) and a lot, at least around here, in meaningless English sold in the Chinese shops (‘I lovve your drum’).

I think my first proper as-we-understand-them-today tee shirt came from

a beach-bar night-club called Trader John’s (better known afterwards as

‘the Congo’) a sort of down-market but lots of fun night spot you would

never either find or would be allowed to operate these days (Spain

having, in my opinion and as far as drinking is concerned, gone to the

dogs). It helped make both the club and indeed Mojácar famous. So

simple: a logo and the name of the joint. Now, alas, lost.

The next one, traces of which are still reposing, in shreds, under

the sink, was another good old and well-loved number which said ‘Relieve Mafeking’.

People would come up, you know, with a well-crafted tee shirt. Why I

should treasure this one is probably best left to me and my confessor.

I’ve gone though loads of these simple yet decorative garments over

the years; sometimes bought but usually acquired free, one way or the

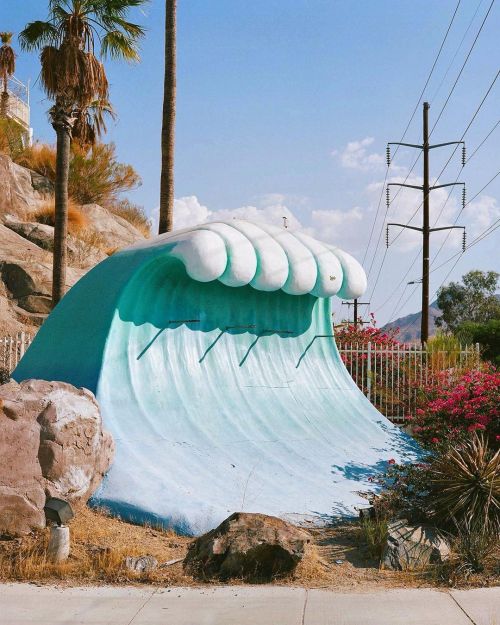

other. The latest, stolen I suspect, is a splendid effort. This one will

never make its way into the rag-box. It’s an artist's inspiration of

what must be Caribbean people dancing away with tom toms and so on, and

the catchy phrase ‘Rasta Riddim’ gaily etched above the illustration. Below, it says ‘Peace, Love, Harmony’.

And below that, perhaps as an afterthought, it says 'Mojácar'.

Even the moths wouldn’t mess with this one.

e

to travel around Spain, perhaps ‘Parador hopping’ or the occasional

shopping trip down to Marbella or Gibraltar - or maybe they prefer to

spend their time at home, gardening or entertaining. This group, as far

as Spain is concerned, is most welcome. They spend freely and they don’t

‘take away anyone’s jobs’. Despite some indignant Facebook posts to the

contrary, I think that the majority of Brits living in Spain fall into

this catagory. These days, there's an unfortunate sub-group among the

long-timers - those who have failed to get their residence papers - the

ones worried now about the precise meaning of the ninety-day rule.

e

to travel around Spain, perhaps ‘Parador hopping’ or the occasional

shopping trip down to Marbella or Gibraltar - or maybe they prefer to

spend their time at home, gardening or entertaining. This group, as far

as Spain is concerned, is most welcome. They spend freely and they don’t

‘take away anyone’s jobs’. Despite some indignant Facebook posts to the

contrary, I think that the majority of Brits living in Spain fall into

this catagory. These days, there's an unfortunate sub-group among the

long-timers - those who have failed to get their residence papers - the

ones worried now about the precise meaning of the ninety-day rule. ible.

How can this be? Shouldn’t all of us, in the decades to come, start to

create our own homogenised way of speaking? Shouldn’t we become,

eventually, something like the two-language-speaking Gibraltarians?

ible.

How can this be? Shouldn’t all of us, in the decades to come, start to

create our own homogenised way of speaking? Shouldn’t we become,

eventually, something like the two-language-speaking Gibraltarians? we

have lots of firewood. Blackened, sooty and dead. It just needs

scooping up, cutting, breaking or uprooting and the chimney is stuffed

to bursting for the evening. Our house is a country-house, nice in the

summer, cold and drafty in the winter. A good fire in the bedroom to

keep everything toasty, but not much use in July. I decide that I shall

once again put off for another day any thoughts of sawing, piling and

sorting the lumber so kindly donated by a passing pyromaniac.

we

have lots of firewood. Blackened, sooty and dead. It just needs

scooping up, cutting, breaking or uprooting and the chimney is stuffed

to bursting for the evening. Our house is a country-house, nice in the

summer, cold and drafty in the winter. A good fire in the bedroom to

keep everything toasty, but not much use in July. I decide that I shall

once again put off for another day any thoughts of sawing, piling and

sorting the lumber so kindly donated by a passing pyromaniac.

business clearly chalked by a previous inmate. There was evidently time to kill.

business clearly chalked by a previous inmate. There was evidently time to kill.

e notices your tie-dyed tee shirt came out a bit wonky.

e notices your tie-dyed tee shirt came out a bit wonky.