How good are you on names? I have a small problem with remembering

them which dates back to school times. I attended a place with eight

hundred other boys, 120 of which were presumably in their leaving year, a

large number somewhere in the middle, and another 120 just arriving.

All dressed in the same uniform and haircut. All to be known by their

last names.

Then there were the masters and the associate staff. And Matron.

There was a little blue book that listed the whole lot of them by house,

name and dates.

There were twelve ‘houses’ of which, by the time I left, I could

confidently locate four. But, the ‘Blue Book’ knew. Some fellows, they

must have been swots, learnt the whole thing and could put the right

name to everybody.

People like that, we knew, would one day excel in public life. Now, I

wasn’t as game at this as I might have been, never knowing by name more

than about twenty people, students and masters, and by sight, perhaps

another thirty or so (plus the tea-lady).

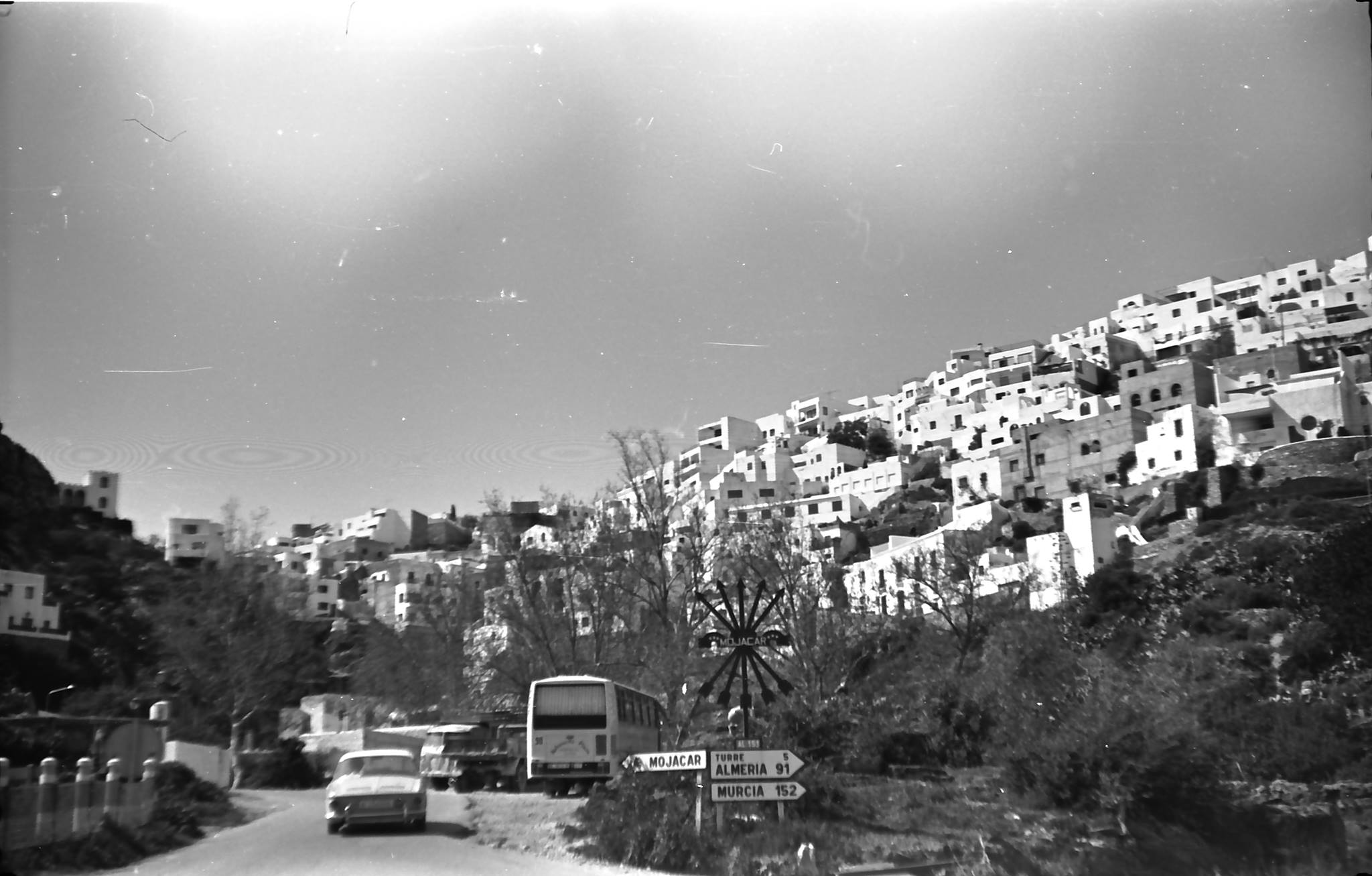

This didn’t prepare me very well for adult life, especially a place like Mojácar which, in a way similar to the old school (‘Gloreat Rugbeia’)

has lots of both new-boys and, indeed, leavers. The difference being,

according to my mum, that here is a lot more like living in a lunatic

asylum.

Where no one knows who the nurses are.

Spain has its own way of dealing with names. While we get by with a

first name, a middle name that no one knows and a last name, the Spanish

go for a first name (un nombre), the more generic the better, and a handful of last names (los apellidos).

Here, a woman’s surname doesn’t change on entering into the holy state

of matrimony (unless the husband’s name is rather smart in which case

she’ll tack it on the end of her own). She’ll keep her old collection

and, if pushed, might accept being ‘la Señora de so-and-so’. Any

children that happen along will take the best bits from their two

parents’ surnames and weld them together into a fresh and different

name. Thus José López Rodríguez marries María Pérez Muñoz, who keeps her name as always it was, and the children are called María López Pérez and José-Luís López Pérez

(who may call himself, quite correctly under Spanish logic, Pepe

Pérez). Or nowadays, they can legally reverse the surnames, with

Mother's monica coming first - thus Pérez López, why not.

Which explains why the Spanish authorities will always want to know

the first-name from one’s parents. Francisco, son of José and Alicia.

You may have noticed that the Spanish are very enthusiastic about our

middle-name, under the impression that it's really a first surname - a

sort of anglo deal where we use our second-surname in an acceptable way,

while quietly dropping the first one.

Which is usually Douglas or Reginald and chosen to honour grand-dad while sublely reminding him about the Will.

Our middle names (God forbid we have several of them) are generally

ignored by both foreigners and the Spanish except when in prison or

hospital and they will always be used in police reports to cause

confusion when leaked to the press (‘Richard Waverly B was arrested

yesterday in connection with…’) or at the hospital ('I'd like to see

Señor uh, Waverly - did I pronounce that right?').

My dad was known as ‘Chick Napier’ at school, not because there were

many others with his name, but because ‘he had eyes like poached eggs’.

Most people in Spain, equipped as they are with first and a variety of

last names, also enjoy an ‘apodo’ or a ‘mote’ – a

nick-name. Somebody goes to work in Germany for six months in 1925, as

happened in Mojácar, and the whole family to this day is called ‘Los Alemanes’. Another well-known family is Los Marullos, and one of them, Francisco Gonzalez ‘el Marullo’, was mayor of Mojácar. Marullo means ‘sneak thief’.

Nobody from around here finds that peculiar. It makes it easier for

people to identify one another. Another family from the hills is known

as ‘Los Pajules’: the tossers. They may make one think of Onan

from the Bible, whose unconventional sexual activities duly (and

inevitably) wiped out his line, but the Pajules clearly have a wider

repertoire, since there are quite a lot of them. In fact, every local

family will have its own ‘apodo’ which, as we have seen, they will be fiercely proud of.

Small towns have a reduced number of ‘apellidos’: surnames.

Here in my town, we have Flores, García, Gonzalez, Haro and a couple

more. I had an employee called Paco Flores (Paco is really Francisco)

and one day I went down to the bank to pay him something. The manager

looked pityingly at me, ‘there’s twenty six Francisco Flores with

accounts here’, he said. Turned out later that my chap wasn’t one of

them anyway, being called Francisco-José Flores instead.

Spaniards, like the Welsh who apparently all share the same surname,

are obliged to invent different nicknames, or just use different

variations of their first name. Francisco can be Franco, Francis,

Pancho, Paco, Paquito, Frasquito, Ico and Fran.

Actually the most famous Pancho of them all, Pancho Villa, was really called Doroteo. Who would have guessed?

A friend called Diego has a sure-fire solution to his poor memory for names. He calls all the men ‘León’ and all the women ‘Guapa’ – Lionheart and My Pretty. It’s so much more elegant than the British ‘Ahhh, this is Errr-um…’

And then, for Goodness Sakes, the Brits expect us to know the names of their children and their dogs as well.

Until ‘La Democracia’ arrived in 1975, you had to call you

child by a nice Christian saint’s name, or two would be even better.

Sometimes a boy’s name followed by a girl’s (which isn’t generally worth

making fun of, unless you can show a good turn of speed). Like José

María. Or, of course, María José. I can’t see those names working at my

old school, even though, since my day, it’s apparently gone

co-educational.

So here in Spain your married parents are separately named (father's

name) (mother's name) and you legally take their two first surnames to

make up your own set. You may use just your father’s name in the street

or, both, or indeed, if your father’s name is a bit humdrum, then you

can use your mother’s surname. Take our former president for example.

He’s called José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero. He nevertheless uses his

mother’s surname. However, his kids won’t technically be able to call

themselves ‘Zapatero’ which is a bit of a swizz. They’ll probably use it

anyway.

Spaniards, for their part, are confused about us having two first

names and one surname, which the ladies among us will change on getting

married. Same surname? They sometimes confuse us as brother and sister.

There are even the equivalents to Thingume, Woosit and Whatyacallim

for those of a forgetful disposition - thus Spain has Fulano, Mengano,

Zutano and my old mate Perengano to hold up the side. Una Fulana, unfortunately, and Spain being how it is, is a name for a whore.

If you are called Juan and you bump into another Juan, you’ll call him ‘Tocayo’ which means ‘namesake’, which in English, as far as I know, doesn’t work.

Of course, I’ve never met another Lenox.

iders. Not me, Gracious no, I was either in the bar or propping up the chiringuito: the temporary tin-bar in the square next to a pop-group platform.

iders. Not me, Gracious no, I was either in the bar or propping up the chiringuito: the temporary tin-bar in the square next to a pop-group platform.