Spain has

an enviable system of describing distances. Rather than kilometres,

they use time. Or they may use rest-stops, cigarettes smoked, the number

of songs from Joan Manuel Serrat listened to (and sung along with) on

the CD player, or even brothels (depending on your route, Murcia to

Almería can be a six-brothel voyage). For shorter peregrinations, I use

dustbins.

I walk the dog each day past four green 'contenadores'. These large bins, together with smaller empty waste-baskets with an inverted bin-liner bobbing merrily out of them, are liberally distributed along my route, as indeed they are all over Spain. There is a tendency of course on the part of the public to eschew the friendly nearby dustbin and just hurl the empty gin-bottle out into the campo, but we try. We try.

Unlike some northern nations, Spain has never held a poor opinion towards rubbish, and it is traditionally thrown on the floor, or out of windows or the open doors. I wonder sometimes if that was why they invented windows - an easy place to discard unwanted trash.

I remember my first shrimp, at the age of thirteen. I dutifully dismembered it, chooped its head and left the reamins on the bar. No, no, pantomimed the barman, flapping his hands, the garbage goes on the floor! And he was right. Under my very feet, a woman was mopping the marble flags and loading the detritus into a bucket. They used to say that one could tell a good tapa-bar by the amount of crap on the floor.

Sometimes, as we are lighting a cigarette or searching for the next brothel in the car (with its garish lights and brutish architecture), we must swerve violently as a surprise missile is hurled out of the window from the vehicle in front. It's usually a wrapper of some sort, or maybe a bottle (can, plastic or glass). Evidently, not wanted on voyage.

When walking the dog, along the side of the road we will find glass, trash, rubbish, human poop (it's a terrible thing to be caught short in the campo), dead things, empty wine bottles (do drivers savour the last drop of the vino before jettisoning the bottle?), plastic sheets and bags, mungy bits of clothing and sundry french letter packets. Then, depending on the neighbourhood, clumps of discarded copies of the free English-language press, some pages of which may have found a final use...

Indeed, as I now live in an area noted for its plastic farms, I see where the old rolls of mangled plastic are left in untidy piles alongside the road, or where bits whip against a piece of barbed wire in the wind, or maybe make their way slowly and majestically towards the sea (often in the back of a truck). In some cases, the plastic sheets are simply ploughed back into the land. Goodness knows what the dog will find on his walk...

For some reason, there is no Spanish version of 'Keep Britain Tidy', even though those contenadores are emptied daily (rather than twice a month as, apparently, the humble dustbin is in the UK). A Spanish friend explained to me once that the bins here need to be emptied regularly 'as we eat fresh food rather than things out of tins' (which seems to be an argument that's hard to refute).

With the exception of rampant litter-buggery, I love Spain.

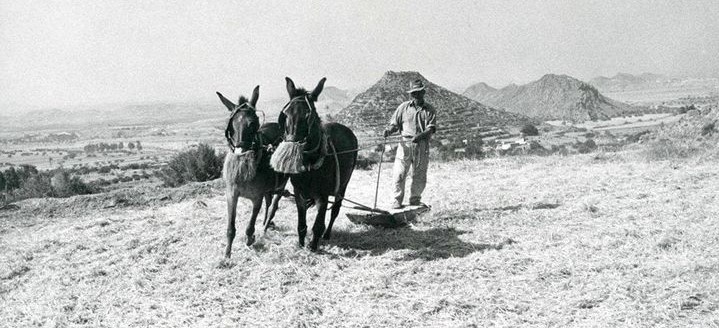

Every farm in southern Spain has something called an 'era'

which is a flat dirt circle, I think called a threshing circle in

English, where the hay would be put after being cut with a scythe. A

wooden board with rows of knife-like wheels underneath was pulled by a

donkey and driven with long-reins by the farmer. Weight must be applied

to the board in order to cut the hay, hence the children. There are

actually several different boards with different types of knifed wheels

for each phase of cutting. It was a very exciting time for the children

when the farmer called them to come and sit on the board while he went

round and round. It takes several days to cut the hay into small pieces

and release the grain from the stalk. It is a sticky job, in the heat

you get covered in pieces of hay and it is a bit like a ride at an

amusement park, bumping up and down it is a rough ride especially when

the hay is in the centre at the beginning, it gets to be a smoother ride

as the hay gets spread around the circle. The board sometimes even

flips over.

Every farm in southern Spain has something called an 'era'

which is a flat dirt circle, I think called a threshing circle in

English, where the hay would be put after being cut with a scythe. A

wooden board with rows of knife-like wheels underneath was pulled by a

donkey and driven with long-reins by the farmer. Weight must be applied

to the board in order to cut the hay, hence the children. There are

actually several different boards with different types of knifed wheels

for each phase of cutting. It was a very exciting time for the children

when the farmer called them to come and sit on the board while he went

round and round. It takes several days to cut the hay into small pieces

and release the grain from the stalk. It is a sticky job, in the heat

you get covered in pieces of hay and it is a bit like a ride at an

amusement park, bumping up and down it is a rough ride especially when

the hay is in the centre at the beginning, it gets to be a smoother ride

as the hay gets spread around the circle. The board sometimes even

flips over.

(Spain:

somewhere on a narrow and dusty road to nowhere). I was driving along

just this side of safe, with one eye on the speedo and the other on the

rear-view mirror. Half asleep and all bored. Then, the mobile phone

rang. One of the kids had been messing with the damn thing so I wasn’t

immediately aware what was going on. The CD was belting out some fine

blues and there was a thin weepy sound running below, just on this side

of conscious. A mild arrhythmia over my heart finally helped me put it

together – the damn phone in my shirt was vibrating and… yes… actually

crying to be answered.

(Spain:

somewhere on a narrow and dusty road to nowhere). I was driving along

just this side of safe, with one eye on the speedo and the other on the

rear-view mirror. Half asleep and all bored. Then, the mobile phone

rang. One of the kids had been messing with the damn thing so I wasn’t

immediately aware what was going on. The CD was belting out some fine

blues and there was a thin weepy sound running below, just on this side

of conscious. A mild arrhythmia over my heart finally helped me put it

together – the damn phone in my shirt was vibrating and… yes… actually

crying to be answered.