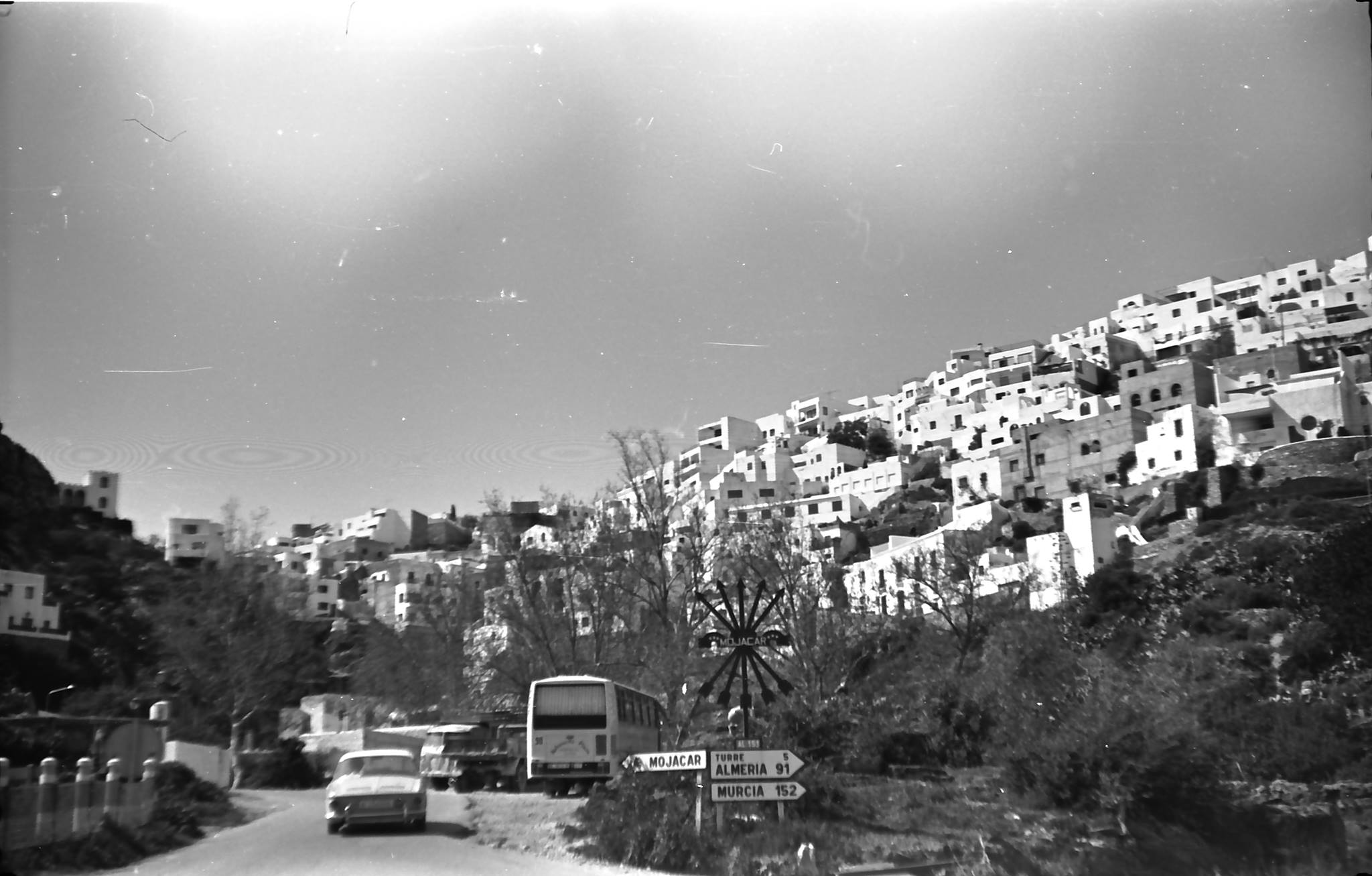

In the past I have often pointed out the difference (and benefit) to

Spanish society between foreign settlers and foreign tourists. While the

settlers are cordially ignored by the authorities (except during the

tax season), foreign tourism receives enormous media attention, massive

investment, endless promotions both at home and abroad, heavy

institutional advertising and even a dedicated government ministry along

with its regional equivalents. In several communities and resorts, the

councillor for tourism is the second most visible politician in the

government.

But then, as Spain basks in the huge amount of money brought here by

tourism (forgetting that a sizable chunk of this stays in the country of

origin to pay agencies, airlines, insurers and so on), along comes

something to put the cork in – maybe a pandemic like the one that has

assailed the industry for the last two years.

If visitor numbers had dropped by 75% in 2021 over 2019 (the last

halcyon year for tourism) the number of foreign residents either stayed

the same (they couldn’t sell-up and leave, what with one thing or

another) or even rose in numbers.

That’s of course not including those few who dared the odds and actually took out Spanish nationality.

There are currently over six million foreigners resident in Spain at

the present time – up from 4,850,000 recorded at the beginning of 2019.

That’s ten per cent of everyone. Some of them are retired, some of them

are living from income from abroad, some of them working and some of

them studying. Some of them here illegally. Some without documents. Some

of them sending their money home to their families, as they should.

While many of the six million are immigrant workers, the largest collectives being Romanian,  Mor

Mor occan and Colombian, the fourth largest group of foreigners currently living in Spain are the British at precisely 282,124 souls.

occan and Colombian, the fourth largest group of foreigners currently living in Spain are the British at precisely 282,124 souls.

Maybe. That's the figure from the padrón - those who are

registered in the town halls across Spain. Other painstakingly accurate

figures for the Brits are quite different. The Government claims 407,628

Brits living in Spain. Statista reckons on 313,975 and the ABC

newspaper goes with 290,372.

All good for December 31st 2021.

Why are the figures so different (and so painfully acquired)? We

imagine teams of dedicated beancounters adding up numbers each time they

go to the market, the expat bar or the dog pound. And then, to show

they weren't making it up, they arrive at those ridiculously exact

figures before locking their desks are rushing out for a coffee.

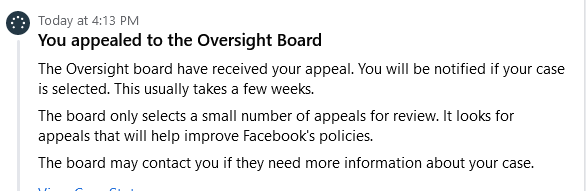

There are other official government sites available, but the browser found a ‘potential security threat and did not continue to www.mites.gob.es’. So, we shall remain blissfully ignorant of the information to be found on that no doubt highly useful page.

Then we have headline from a silly English-language newspaper from

last October which claimed that British expats are said to be leaving

Spain "in droves"; while, conversely: the property site Idealista was

posting the opposite: ‘The Brits bought 7,560 homes in the second half

of 2021 – the largest group of foreign buyers’, they said.

With all the confusion, the authorities will understandably react

according to the figures to hand (once they’ve successfully looked up

the phrase ‘in droves’ in the dictionary), without worrying if

they are correct; or maybe just go out for another coffee instead. Of

course, looking out of the window in an office in Madrid, one won't see

many Northern European residents. They tend to live in a wash of small

pueblos along the coast and on the islands. Even then you probably won't

notice them - or confuse them with tourists - unless you happen to be

trying to sell something to the director of the local medical centre.

In all, nearly 64,000 homes were bought by foreigners between July

and December last year. And that’s good money brought here almost

exclusively from outside Spain.

So we come back to our original doubt - why does Spain chase the foreign tourist and ignore the foreign resident?

Rather than try and figure out the number of foreign residents who

are retired or live from funds from abroad (including a clutch of

wealthy Americans, some rich Venezuelans, a few idle Chinese and a

sprinkle of superannuated New Zealanders), but not Tommy who works at

the campsite, we can only choose a wildly inaccurate number – say

500,000 – to contrast with the tourists, whose statistics thanks to the

enormous machine dedicated to surveying them we know down to the last

digit.

Figures suggest that the average age of this sub-group of half a

million – that’s to say, those who live comfortably in Spain without

employment – is around 61 years old, against tourists who are (I’m

diving through the INE records) maybe 20 years younger.

Then of course, residents often take trips within Spain – not to

all-inclusive hotels on the beach, full of fellow-Brits or Europeans,

but to more expensive destinations, such as the Parador hotel chain or

to fancy restaurants, or to areas away from the sol y playa; which makes them, in the eyes of the Spanish authorities (if only briefly), tourists.

So, if the money spent by just the wealthier foreign settlers –

500,000 multiplied by a year’s worth of living – is contrasted by the

amount spent by the tourists, then the residents are clearly a group to

treasure. At 20,000€ a year (my guess, and we shall ignore the major

investment of buying both a 250,000€ house and a car) that’s

10,000,000,000€ per year spent by the higher end of the resident

foreigners in Spain. The average visitor, here for five days rather than

365, is going to be worth a lot less.

But you won’t find any official agency or policy that promotes foreign home-buyers investing in Spain!

Tourists, then, are described as anyone foreign who comes to Spain

(even if they are taking an onwards flight to somewhere else and never

even leave the airport), plus all the people on all the cruise ships –

regardless of if they disembark for a two-hour stroll around Málaga

harbour or not – plus all the people who hop over to Spain every weekend

(add ’em all together José), but not the ones who drove across the

frontier or who slept in the guest room last night or on the sofa.

Then we have those non-EU citizens (now including a large number of

Brits) who own homes here are but aren’t allowed to stay for more than

90 in any 180 day period. What are they exactly – residents,

home-owners, tourists? No one knows or seems to care – except of course

for the affronted local businesses.

Following the pandemic, we now have a terrible war and next up

perhaps, a tourist bombing, or an earthquake, or something poisonous in

the water. Maybe Portugal will drop its prices or Greece will give free

ouzo to visitors. Tourists are just fine, they leave money and go away

with a sunburn and a hangover. But they are finicky, and without any

obligation or an emotional link to return.

But the residents will stay. They have an investment in Spain: their property.

Why can’t the authorities see this? There is so much more opportunity in this field.

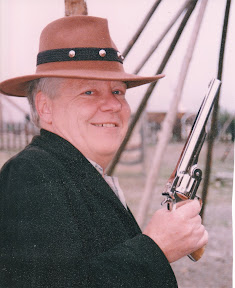

iders. Not me, Gracious no, I was either in the bar or propping up the chiringuito: the temporary tin-bar in the square next to a pop-group platform.

iders. Not me, Gracious no, I was either in the bar or propping up the chiringuito: the temporary tin-bar in the square next to a pop-group platform.

owboy

hat and a revolver and take a picture of you looking either mean or

else bemused (or in my case, mildly sun-stroked and drunk).

owboy

hat and a revolver and take a picture of you looking either mean or

else bemused (or in my case, mildly sun-stroked and drunk).

d

be that a few of those, attracted by our weather, will head in this

direction, their cheque book and the phone number of a really good

lawyer in their inside-pocket.

d

be that a few of those, attracted by our weather, will head in this

direction, their cheque book and the phone number of a really good

lawyer in their inside-pocket.

Mor

Mor